For three decades after the second world war, US scientists and doctors carried out a research programme of striking ambition – and breathtaking moral negligence. They deliberately infected more than 1,000 people, including at least 100 children, with hepatitis, an illness that can trigger chronic liver disease and cancer.

Very few of those subjected to this experimentation had much idea of what was being inflicted upon them. Many were poor and uneducated and came from prisons, asylums and orphanages. A disproportionate number were black.

“I know of no series of problematic infectious disease studies that involved a wider array of devalued and stigmatised groups,” Sydney Halpern tells us in this chilling, unsparing account of a mass experiment that violated the rights and health of America’s underprivileged from 1942 to 1972.

Subjects included prison inmates, draft objectors who were already derided as “yellowbellies” and adults and minors with intellectual impairments. “The use of such a broad range of marginalised groups is astounding,” adds Halpern, a US sociologist and bioethicist.

The fact that this mass violation of human rights continued for so long is perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of this story. How could these decades-long trials have been permitted in a society that believed itself to be untainted by crimes that had typified its Nazi opponents?

Halpern is at pains to find rational answers to such questions, but in the end struggles to find coherence in the motives of the scientists involved or to discover any doubts they may have had about the ethics of their behaviour. The nation had allowed the creation of a military-biomedical elite that decided the need to control disease and defend the nation justified actions that clearly led to the early deaths of innocent people. Worse, they were largely supported by a supine, deferential press.

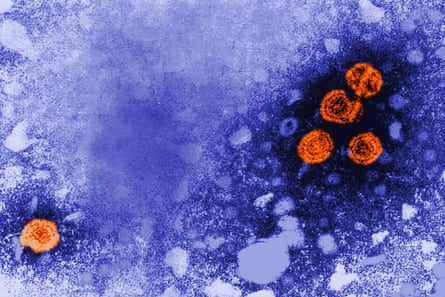

Hepatitis is a disease characterised by inflammation of the liver, jaundice, fever and exhaustion and is most commonly caused, we now know, by viruses of which there are five variants: A, B, C, D and E. In some cases, those infected can develop cirrhosis and liver cancer in later life.

In 1942, a major outbreak occurred among US soldiers. This was traced to a contaminated batch of yellow fever vaccine whose serum had been derived from hepatitis carriers. Scientists decided to take advantage of these sullied samples and used them to infect men, women and, later on, children in a bid to understand more about hepatitis.

These studies were expanded over the decades, with researchers persuading their recruits to directly ingest samples of tainted material. These included milkshakes made from infected human excrement mixed into chocolate milk in a bid to conceal its true contents. “What scientists did was create a pool of hepatitis carriers at risk for slowly simmering, life-threatening liver diseases,” writes Halpern. Just how many died as a direct result of the US hepatitis programme is unclear, so clandestine were its operations. Undoubtedly, there would have been fatalities.

Not all these dangers were known when the hepatitis programme began, Halpern acknowledges. Yet even when they did become evident, no one bothered to try to trace those who had developed liver disease or pinpoint those who had died because of scientists’ actions.

In the end, the programme was brought down by 1960s activism. Campaigns against the Vietnam war and for minority rights heightened sensitivity to the actions of the authorities and young doctors began to question the programme with increasing vigour. “I moved easily from civil rights to patients’ rights,” one young doctor told Halpern. The programme ended, effectively, in 1972.

Halpern’s story is chilling, told with clarity and commendable brevity and, most importantly, is of crucial relevance today. The emergence of Covid-19 galvanised calls for the creation of experiments in which volunteers would be infected with SARS-CoV-2 to help understand how the disease spreads and behaves. Some of these studies continue.

But as she warns, the long-term consequences of infection are unknown and are not likely to be fully understood for years. “It is therefore vitally important to understand human experiments with dangerous viruses during a previous emergency.” America’s hepatitis programme has a lot to tell us from that perspective.

Dangerous Medicine by Sydney Halpern is published by Yale University Press (£25). To support the Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Delivery charges may apply